From OpenAI API Compatibility APIs to MCP-Compatible Agents: An Evolution in AI Integration

Table of Contents generated with DocToc

- From OpenAI API Compatibility APIs to MCP-Compatible Agents: An Evolution in AI Integration

- Early Popularity of OpenAI-Compatible APIs

- Limitations of OpenAI API Compatibility in Advanced Workflows

- Introducing MCP: A Protocol, Not a Runtime

- Beyond the API: How MCP Unlocks Control and Interoperability

- OpenAI-Compatible API vs. MCP-Compatible Agent

- Conclusion: Ecosystem Evolution and Future Outlook

From OpenAI API Compatibility APIs to MCP-Compatible Agents: An Evolution in AI Integration

Early Popularity of OpenAI-Compatible APIs

In the early days of large language model (LLM) adoption, OpenAI’s API format emerged as a de facto standard for interacting with chat models and completions. Developers gravitated to OpenAI’s RESTful API for its simplicity and consistency, and many tools and libraries were built to speak the “OpenAI dialect”.

This popularity led to a proliferation of OpenAI-compatible APIs offered by third parties or open-source projects. For instance, frameworks like LiteLLM and FastChat provided proxy servers that mimicked the OpenAI API, allowing developers to swap out the actual LLM backend with minimal or no code changes. In practice, this meant that an application written for OpenAI’s v1/chat/completions endpoint could be pointed at a local model (Vicuna, Llama, etc.) or alternative service simply by changing the base URL, with no changes to the request payloads or parsing logic.

This compatibility layer was transformative for rapid experimentation. Using LiteLLM’s proxy, for example, a team could route some requests to OpenAI’s GPT-4, others to Anthropic’s Claude, or even to open models like Mistral, all behind a unified OpenAI-style API interface. FastChat offered a similar solution: it exposed a local API that conformed to OpenAI’s specification, so even LangChain-based apps could transparently switch to local models. These tools eased vendor lock-in concerns and catalyzed a rich ecosystem of plug-and-play LLM backends, where developers felt confident that if a model spoke the OpenAI API, they could integrate it with their existing codebase in minutes.

Limitations of OpenAI API Compatibility in Advanced Workflows

However, as the community ventured into more advanced AI workflows, like chaining multiple model agents together, integrating real-time tools, or enabling agents to collaborate, the cracks in the OpenAI-compatible approach became apparent.

The OpenAI API was designed around single-turn or single-chat interactions, usually involving one primary model completing a task given some prompt and context. Building a multi-agent system with this means each agent is just another API call. The developer must orchestrate these calls, pass messages between agents manually, and maintain any shared state externally.

In other words, the OpenAI API gives you a good LLM-as-a-service, but not a built-in way to have multiple LLMs coordinate or share memory. One major limitation is state and memory: OpenAI’s endpoints don’t provide long-term memory beyond what you explicitly pass in each request.

For multi-agent systems that need to remember prior interactions or a shared world state, developers had to implement external memory buffers or vector databases. Another issue is that the OpenAI format (even with the newer function-calling feature) assumes a fairly fixed sequence: you send a prompt, maybe the model calls a tool via function, then it returns a final answer. Complex workflows where agents converse with each other, or where one agent supervises/monitors another, require a lot of custom glue code around the API.

Additionally, the lack of a control or monitoring channel in OpenAI’s API means you cannot easily intervene in an agent’s reasoning process. For example, if Agent A and Agent B are chatting to solve a problem, using only OpenAI APIs you’d likely implement this by alternating calls (Agent A’s turn -> get completion -> feed into Agent B’s prompt -> get completion -> and so on). There is no straightforward way to intercept this mid-way, inject an external command (like “Agent C says stop now”), or observe intermediate thoughts except by parsing the text generated. This is serviceable, but brittle and opaque.

As multi-agent research progressed, it became clear that a more robust approach was needed for agents to coordinate, share data, and be externally directed or observed. Even OpenAI’s own advancements hint at these gaps. In 2024–2025, OpenAI began introducing an Agents SDK and Azure rolled out an Assistants API to better manage multi-step tool use and agent interactions. These solutions layer new abstractions on top of the basic API to support agent orchestration. For instance, the OpenAI Agents SDK provides features like multi-agent orchestration and agents calling other agents as tools.

Yet, as one early adopter observed, it “currently lacks an MCP … tool and memory support in some scenarios,” which can make handling complex tasks challenging. In short, while OpenAI-compatible APIs were great for swapping out models, they were not designed to handle multi-agent systems or rich integrations in a first-class way.

Introducing MCP: A Protocol, Not a Runtime

The industry’s answer to these challenges is the Model Context Protocol (MCP). Announced by Anthropic in late 2024, MCP is not a single piece of software or a hosted service – it’s a protocol specification (with SDKs) that any AI agent or tool provider can implement.

Think of MCP as analogous to USB or HTTP but for AI agents. As the official documentation puts it, “MCP provides a standardized way to connect AI models to different data sources and tools, like a USB-C port for AI applications.”

This means MCP defines how an agent (or an LLM application) can expose or consume functionalities such as tools, memory storage, or data access in a uniform, interoperable manner. It is not an agent framework itself – you don’t “run MCP” as an alternative to your code. Instead, you implement MCP support in your agents or in external services so they can all speak a common language.

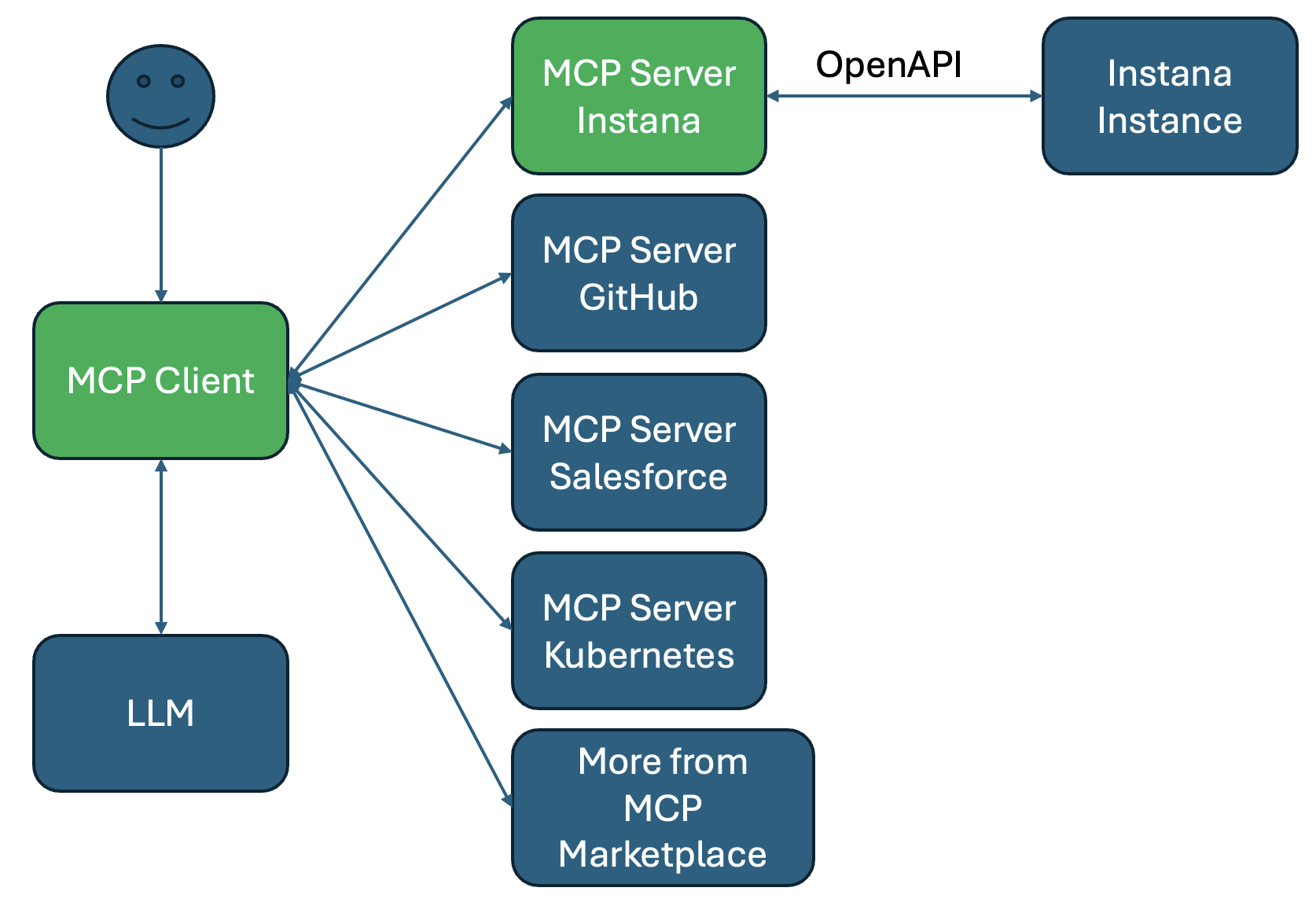

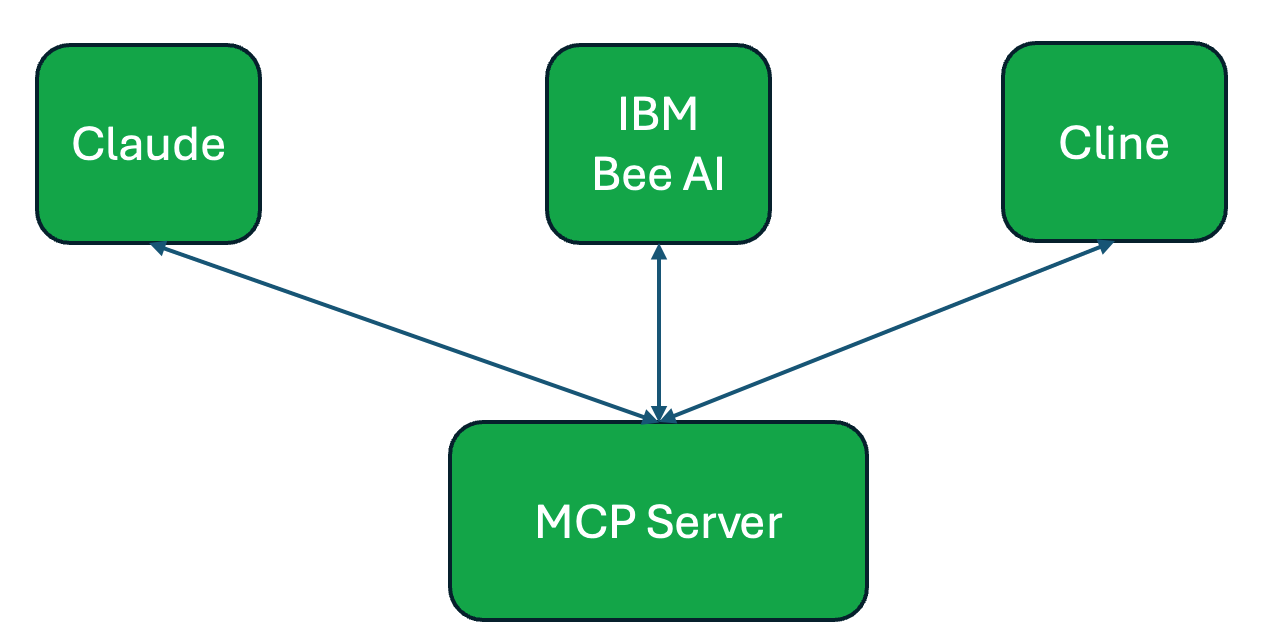

At its core, MCP uses a message-based protocol (built on JSON-RPC 2.0) to enable two-way communication between AI agents (clients) and external services (servers). This design draws inspiration from things like the Language Server Protocol in the developer tools world, which standardized how editors and language analyzers communicate. Similarly, MCP standardizes how AI systems can dynamically discover and use external capabilities. An agent that is an MCP client can connect to any number of MCP servers, each server providing a set of capabilities – these could be tools (i.e., actions the agent can invoke), resources (data or context the agent can read), or even prompts/templates that can be pulled in.

For example, consider an AI coding assistant that needs to access a company’s internal documentation. Traditionally, you might hard-code an API call to a documentation database or vector store. With MCP, the documentation team could stand up an MCP server that exposes a searchDocs tool and a CompanyKnowledgeBase resource. Any MCP-enabled agent, regardless of which framework or LLM it uses, can connect to that server and query it in a standard way. The protocol abstracts away the specifics of the database or authentication, so from the agent’s perspective, it just sees a new tool named “searchDocs” became available and knows (from the MCP metadata) how to call it. It’s important to emphasize that MCP is model-agnostic and framework-agnostic.

An agent built in Microsoft’s AutoGen framework can use MCP to call a tool implemented in Python that interfaces with, say, a Jira API. A research project using LangChain or LangGraph can equally consume that tool via MCP. This open standard approach has gained significant momentum; within a few months of launch, thousands of community MCP servers (connectors) for various services have appeared.

Companies like Block, Replit, Zed, and Sourcegraph quickly embraced MCP as a way to let their AI features interoperate with other systems. Unlike earlier attempts at standardization, MCP has the backing of a major AI lab and a rapidly growing open-source community, positioning it as a likely common denominator for agent-tool integration going forward.

Beyond the API: How MCP Unlocks Control and Interoperability

What does adopting MCP enable that wasn’t feasible with a vanilla OpenAI-style API? For one, agents become externally controllable in ways not previously possible. Because MCP defines a channel for structured communication, a third-party “controller” could instruct an agent or read its state through an MCP interface. For instance, an MCP server might expose a tool like pauseAgent or getAgentStatus for a running agent. A monitoring dashboard (another client of MCP) could call getAgentStatus periodically to retrieve the agent’s internal metrics or progress, something that would have been a hacky afterthought in the OpenAI API world. Another key aspect is shared memory and knowledge. Under the MCP paradigm, memory can be externalized as a service. Imagine an agent that is part of a team of agents: you could have a dedicated Memory MCP server that all agents use to store and retrieve facts, conversation history, or intermediate results. This effectively gives them shared memory access.

In practice, one agent can push information to the memory server (e.g., “remember outcome X associated with task Y”), and another agent can later query it, all through the MCP protocol. Because it’s standardized, the memory server doesn’t need to be built into the agents’ codebase; it’s a plug-and-play component. This greatly contrasts with the OpenAI API approach where each agent’s memory was either ephemeral (in its prompt history) or manually integrated via some common database. MCP also promotes a modular architecture. You can have specialized MCP servers for specific domains – one for web browsing, one for database queries, one for emails, etc. Agents can dynamically discover what tools and resources are available and use them as needed. This dynamic discovery is a game-changer: rather than hard-coding every possible tool an agent might use, the agent can query an MCP registry or simply listen on a port and be told “here are the 5 tools you now have” at runtime. It’s analogous to how a computer’s OS can detect new hardware or how a browser can load plugins – in the MCP world, an agent can load new “capabilities” on the fly, without a redeploy or code change, as long as those capabilities speak MCP.

Crucially, MCP decouples the control plane from the agent’s internal logic. In advanced scenarios, you might have a human supervisor or an automated system that needs to steer an agent (for safety or efficiency). MCP provides hooks for this. The agent could expose a control interface (as an MCP server) that allows authorized clients to send commands or constraints. For example, a “budget manager” module could connect to an agent and enforce a rule like “do not call the expensive tool more than 3 times,” or a human operator could inject a message like “explain your last step in detail” to an agent through a special MCP tool. These sorts of interactions are outside the scope of what the OpenAI API alone can do, because they require a richer communication channel than just prompt -> completion.

OpenAI-Compatible API vs. MCP-Compatible Agent

To summarize the differences between the old paradigm (OpenAI-style LLM APIs) and the new paradigm (MCP-enabled agents), the table below highlights key points of comparison:

| Aspect | OpenAI-Compatible LLM API | MCP-Compatible AI Agent |

|---|---|---|

| Core Purpose | Provide a standardized interface to a single LLM for completions or chat. Typically one model responds to one prompt at a time. | Provide a standardized protocol for an agent (which may involve multiple LLMs or tools) to interact with external systems and other agents. |

| Interoperability | High interoperability at the API level for model swapping – any service mimicking OpenAI’s endpoints can be used interchangeably. However, limited to whatever functionality the OpenAI API supports (completion, chat, embeddings, etc.). | High interoperability at the capability level – any agent or tool that speaks MCP can work together, regardless of which AI framework or model is underneath. Allows mixing and matching different agent frameworks and tools in one coherent system. |

| Tool Use & Plugins | Supports static integration of tools via function calling (OpenAI Functions) – tools must be predefined and the model decides when to call them. No built-in discovery of new tools at runtime. | Supports dynamic tool discovery and use – agents can fetch available tools from MCP servers at runtime. Tools/skills are treated as services that can be independently developed and plugged in. Plugins (MCP servers) can be added or removed without changing the agent’s code. |

| Multi-Agent Workflows | Not inherently supported; requires orchestrating multiple API calls from an external program. Each agent (model) is isolated – sharing state means manual intervention (e.g., combining prompts). Collaboration patterns (like agent chatting) must be hand-coded. | Natively supports multi-agent orchestration. Agents can communicate via shared MCP channels or use common MCP-accessible resources (shared memory, task lists, etc.). One agent can directly invoke another agent’s functionality through MCP, enabling complex workflows of conversations, delegations, and supervisory control. |

| Typical Use Cases | Straightforward single-task completions, Q&A, content generation, or chaining calls in a fixed pipeline (e.g., summarize text then analyze sentiment). Suited for when one LLM is doing the heavy lifting and tool use is limited. | Complex workflows involving multiple steps, conditional decisions, and interactions with various data sources. Examples: an autonomous research assistant that reads documents, saves notes, asks other agents for help; a multi-agent system where one agent plans and delegates sub-tasks to specialist agents (coding, web browsing, etc.), all coordinated via MCP. |

Conclusion: Ecosystem Evolution and Future Outlook

The shift from OpenAI-compatible APIs to MCP-compatible agents marks a significant evolution in the AI developer ecosystem. In the early phase, the priority was to make different models and services interchangeable, hence the focus on replicating the OpenAI API. That solved a critical problem, allowing the community to experiment with new models easily and avoid vendor lock-in. But as applications grew more ambitious, involving not just one model responding to a user, but multiple models, tools, and data sources working in concert, a higher-level interoperability was needed.

MCP fills that void by standardizing the way these components connect and share context, much like how microservices in software standardized communication between different application components. With MCP, we gain observability and modularity that simply wasn’t feasible before. Developers can now instrument their AI agents almost like we do distributed systems, logging events, monitoring performance, swapping in new modules, all through a common protocol. This opens the door to better debugging of AI decisions and more trust in deploying complex agent systems, because we’re not flying blind; we have a window into the agent’s actions and the ability to shape them.

The ecosystem is already responding. We see previously siloed AI frameworks converging: a LangChain agent can use a tool from a LangGraph agent, or an AutoGen agent can plug into a CrewAI-managed workflow, all thanks to MCP’s agent interoperability. This trend suggests that future AI solutions will be composed of many specialized agents and services, coordinated through protocols like MCP. Instead of one monolithic model trying to do everything, the “ensemble of agents” approach will dominate, where each piece can be independently developed, audited, and improved.

Looking ahead, one can imagine an AI agent marketplace or hub, where third-party developers publish MCP-compatible agents/tools (for example, a data analysis agent, a legal reasoning agent, a graphic design agent) and others can incorporate them into their products with a few lines of code. This is analogous to how web APIs or SaaS services are consumed today, but with a level of fluid integration that’s more dynamic, agents can truly work together rather than just sequentially calling each other’s APIs. It’s also worth noting that while MCP is gaining steam, it’s part of a broader movement toward open protocols in AI. There may be other standards or complementary protocols that arise (for instance, for model-to-model communication or specific domains like robotics).The existence of MCP, however, has set a precedent: future AI development will prioritize interoperability and control as much as raw model capability. We are moving from an era of isolated, black-box large models to an era of collaborative, transparent AI agents.

In summary, OpenAI-compatible APIs will likely remain relevant for what they do best, providing access to powerful singular models. But the center of gravity is shifting to agent-oriented systems. MCP’s emergence as a protocol for multi-agent coordination and tool use is unlocking new levels of functionality. It gives developers the building blocks to create AI systems that are more integrated with the real world, more extensible, and easier to manage. As this ecosystem matures, we can expect faster innovation: teams will focus on crafting specialized agents or tools, knowing they can plug into larger workflows via MCP. The agent ecosystem is heading toward a highly modular, interoperable future, and MCP (and protocols inspired by it) are leading the way in making that future a reality.